By Talibah Chikwendu, Special to the AFRO

To migrate is to move, from one place to another, permanently or temporarily and sometimes back and forth between places. For Blacks, this movement has been across town, states, regions, and even other continents. This year, the Black History Month theme focuses on the movement of Blacks from the 20th Century to today and the impact of that movement.

In the years following the Emancipation Proclamation, which opened travels to Blacks with less danger of abduction and enslavement, most stayed caught in the Southern plantation economy. Many made their living doing the same jobs or providing the same services they had during slavery and found the conditions just as challenging. It was difficult for Blacks to purchase land or start businesses and their hard work life with low pay left them little time to enjoy their freedom.

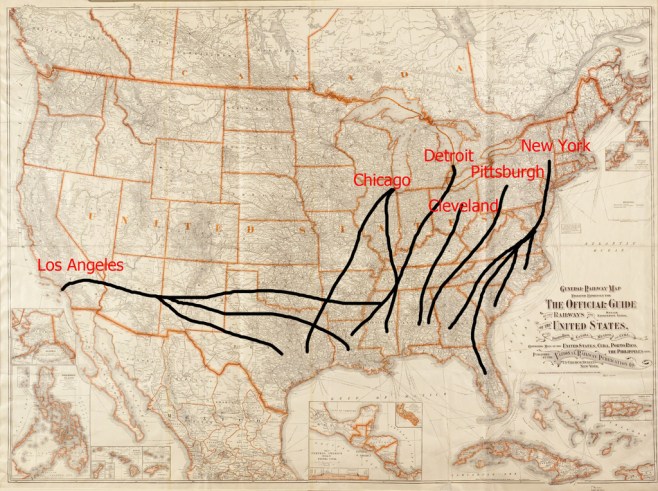

A general railway map from 1918 now shows a few of the migration patterns and destinations of Blacks during the Great Migration. (Map from Library of Congress online collection)

According to James N. Gregory, in his book The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America, only 8 percent of Blacks lived outside the South in 1900, but by 1970, that number had grown to 47 percent.

Dr. George D. Musgrove, historian, author and associate professor of history at University of Maryland Baltimore County, said migration increased earning potential, improved access to voting, provide more political power and proved relatively freer (related to movement). To achieve these benefits, Blacks had to overcome a multitude of challenges, some of these addressed by the offers of Northern companies to pay their way. Whatever the reasons, the Black Migration “transformed the country’s African-American population from a predominantly southern, rural group to a northern, urban one,” according to the Library of Congress African-American Mosaic section on migration.

This shift in the Black population took place in approximately four mass movements. The first was during World War I, of approximately a half million people. The second was during the 1920s, of almost a million Blacks. A smaller wave left during the 1930s. The largest movement, influenced by the information of success coming from the previous movements, took place between 1940-60 with approximately 3.5 million Blacks branching out to other parts of the country.

While the initial movement of Blacks was to large Northern cities – New York, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Detroit – subsequent migrations included more Western destinations, including Los Angeles, Oakland and San Francisco, Calif. and Portland, Ore. and Seattle, Wash. Musgrove pointed out that these migrations were not random, saying that Cleveland, Ohio became Alabama North, while Los Angeles, Calif. was the likely destination for people from Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi.

Musgrove, a Baltimore native and 1997 UMBC graduate, said “It makes the race problem, which for many Northerners was something they could look to as being elsewhere . . . after the Great Migration it is a national phenomenon. It’s not simply a regional phenomenon.”

Segregation is one of the first ways Black migration changed the national landscape. Restrictive covenants related to land transfers and rental agreements were using sparingly, according to Musgrove, until after the first migration. With increased access to the vote and the U.S. taking a stand internationally against the “master race theory,” Northern Blacks use all available avenues to push for Civil Rights.

The migration of Blacks changed the places they ended up and the places they left. “They changed everything,” said Marilyn Hatza, Maryland Lynching Memorial Project board member. “They reshaped these cities.”

From the places they left, Hatza posits, they took their culture and language, and when over 5 million people “pick up and leave the only home they ever knew” it changes a lot. “They even changed the architecture,” said Hatza, who is also a member of the Maryland Commission on African American History & Culture. As Blacks moved to Northern areas, they ended up in the oldest parts of the cities where investment had stopped. According to Hatza, as that housing stock crumbled, it was often replaced with high-rise building projects.

These kinds of impact showed up across the United States and gave rise to a change in political approaches to racism. From the Black Panther Party, to MOVE, to the Pan-Africanism Movement, to the Civil Right Movement, to the Congressional Black Caucus and others . . . all sought to mobilize Black power – political and economic – to eliminate racism and economic oppression. These migrations, especially as they sparked increased segregationist policies across the United States, kept Black influence concentrated, which made it easier to get Black officials elected and Black voices heard.

Hatza and Musgrove commented the reverse migration of last 40 years, with Blacks returning to the South. Musgrove, while not pessimistic, commented that this new migration pattern weakened Northern cities and African-American political power centralized there. His concern is that it will take a while – he posits a decade and a half – to rebuild this political influence in the new locations.

While Hatza doesn’t think reverse migration will relocate as many people, the change is being reflected in the “complexion of the politicians.” She said, “I have hope.”