By Ralph E. Moore

Special to the AFRO

The legendary pitcher, Satchel Paige, once said to Luther ‘Luke’ Atkinson, “You are a second baseman, go play second base!” And with that no nonsense command, the Wilson, N.C. 21-year old was off to a career in Negro League Baseball. Atkinson worked in the Purina grain mill to earn a living (paid $120 a month). And his understanding, baseball-loving boss worked with him on scheduling, so he could get on the bus and play some away games for the Satchel Paige All Stars, named for the legendary then player-coach.

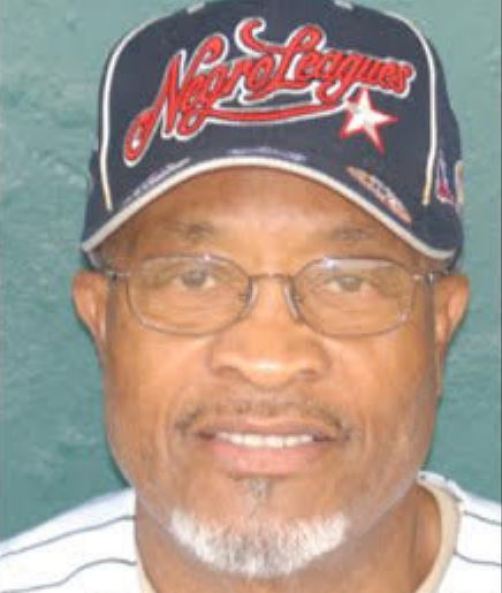

Luther ‘Luke’ Atkinson. (Courtesy Photo)

“ We didn’t know we were making history. We were just trying to get to the next level,” Atkinson said in an interview. “Hats off to Jackie Robinson. He broke into the Major Leagues alone. We tried to do it as a team.” Playing baseball was a life changing experience for me,” Atkinson said the team had a bus but they couldn’t stop to eat certain places. “We ate on the bus or brought along food that wouldn’t go bad.” The Satchel Paige All Stars, were young men coached by the more senior Paige. They could hear harassing, racist remarks on the road to games and at rest stops. But “we couldn’t react to what we heard, Atkinson said. “Coach Paige always told us, ‘Take it out on that white ball!’” That’s what he meant when he said, “I grew up on a baseball diamond.”

He played baseball for five years (1955 to 1960) before he was drafted into the army. Upon returning home, he awaited calls from Major League Baseball teams but he got none. Paige himself played for the Major Leagues with the Cleveland Indians starting in 1948.

In the meantime, Atkinson was signed with the Glenarden Braves in the Continental League, a proposed league within major league baseball that disbanded soon after it started. So 1964 was his last year as a professional baseball player.

Atkinson got an apprenticeship with the Government Printing Office in D.C. and worked there for 39 years.

Atkinson really knows Negro League Baseball. “We didn’t make a lot of money. We were paid from the gate.” In other words there were no big salaries or signing bonuses, no endorsements, no souvenirs to sell or pieces of the television or radio rights. Negro League Ball players hung signs up on poles announcing their games. But he suffered no illusions, “Satchel was the drawing card. They mostly came to see his pitching (he was a player-coach). They knew he had good talent.”

Atkinson can name the three women who, as groundbreakers, played in the Negro League: Toni Stone, Connie Morgan and the most famous of them, Mamie ‘Peanut’ Johnson, nicknamed by an opposing male batter for her 5’3” frame. She struck him out in appreciation for the new name. Atkinson said Mamie thought playing baseball in the League was great; her team was the Indianapolis Clowns. She told him she was treated with the respect due a great pitcher. And there were no problems from the men, she told him.

Atkinson also knew Baltimore treasure, Leon Day, a way above average and versatile Negro League player, who lived for a while and died in Baltimore. He remembers the Baltimore Black Sox and the Baltimore E-lite Giants teams of the Negro Baseball League.

He has lived in Maryland since 1966 and is settled now in White Plains, Md. He coached Boys and Girls Club baseball for four years and hopes his players learned the same life lessons the diamond taught him.

Luke Atkinson will be keynote speaker for the Black History Month Celebration Program at Live! Casino & Hotel, 6-9 p.m., Feb. 20.

The opinions on this page are those of the writers and not necessarily those of the AFRO.

Send letters to The Afro-American • 1531 S. Edgewood St. Baltimore, MD 21227 or fax to 1-877-570-9297 or e-mail to editor@afro.com