By Stephen Janis and Taya Graham, Special to the AFRO

It was never really a choice for Tawanda Jones.

The Baltimore activist whose brother died after a brutal police beating in 2013 faced a decision that a decades old city policy had foisted upon families who sued the Baltimore Police Department (BPD) and won.

The deal was, participate in a financial settlement as the result of the lawsuit, but keep your mouth shut.

For Jones, who faced that decision in 2017 when the city offered a $1 million settlement to her family, it was not an option.

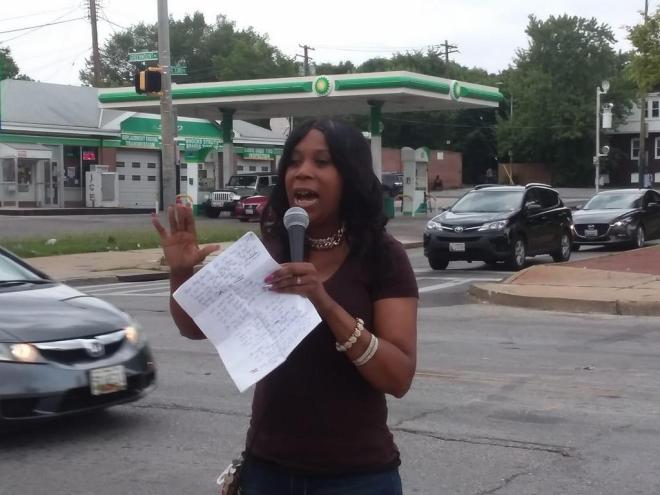

Tawanda Jones, a leader in the law enforcement reform movement has been fighting for justice for her brother Tyrone

West, since he died in police custody in July 2013. Now, new Baltimore legislation may eliminate the city imposed gag

order that prevents those victimized by police brutality who win lawsuits from speaking out. (Tawanda Jones, Facebook)

“It would kill me not to speak about what happened to my brother,” Jones told the AFRO.

In fact, Jones has been one of the most outspoken voices against the policy, having held over 312 consecutive protests every Wednesday to mark her brother’s death and to call for the police who allegedly killed him to face punishment.

“You can’t put a price on a life and forced silence is legalized violence,” she said.

But, for countless others, the policy of city-imposed gag orders have translated into taxpayer purchased silence that many say has done more to hide the misdeeds of the police than any other policy implemented by the city.

And now a group of city lawmakers led by Councilwoman Shannon Sneed aims to ban the practice.

Legislation introduced July 22, will prohibit the city from cutting back room deals to silence victims. It’s a move the councilwoman touted as a step in the right direction for a city that has been struggling to right a department often at odds with the community.

“We are standing together so that no longer will settlements stop us from telling our truths,” Sneed said.

Baltimore City Council President Brandon Scott said gag orders bypassed a critical mechanism for reform, transparency.

“If we truly want to reform the police department we need to end these policies,” Scott told the AFRO.

One question looming over the announcement was if the bill had the support of Mayor Jack Young. “I will abide by whatever the solicitor (Baltimore City Solicitor Andre Davis), tells me as far as that is concerned,” Young said.

Other questions also remain unanswered; will the new law be retroactive, freeing past victims of brutality who were forced to sign non-disclosure forms to speak about their experiences?

The legislation comes after a landmark decision by the federal Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled Baltimore’s practice of requiring non-disclosure by plaintiffs as part of settlements was unconstitutional. The suit was filed by the Maryland ACLU on behalf of the Baltimore Brew, a local news website.

“We are coming together to reimagine a First Amendment that belongs to all residents of Baltimore. This must include Black and Brown residents, who are too often racially profiled and brutalized by police,” said Executive Director of the ACLU of Maryland, Dana Vickers Shelley.

But for the city’s top lawyer Andre Davis, the question is not settled. On Monday Davis filed a petition to have full circuit panel of fifteen judges review the decision and overturn it.

“The panel majority in this case has redefined the very meaning of liberty, infantilized less wealthy litigants even where they are represented by counsel of their own choosing, and made it categorically impossible, as a matter of federal constitutional law, for state and local government employees to protect their interests,” city attorneys wrote in the petition.

Meanwhile, as city officials debate the future of gag orders, a recently released report by the team tasked with monitoring the progress of implementing a federal consent decree with the BPD was sharply critical of recent lapses in holding officers accountable.

The report contends that not only has the department failed to complete a long-promised investigation into the root causes of the Gun Trace Task Force scandal, but has not yet authorized it.

The Gun Trace Task Force was a group of eight officers who were convicted or pled guilty to robbing residents, dealing drugs, and stealing overtime.

That miscue, along with a recent dismissal of 12 serious cases of sustained internal affairs complaints after statute of limitations expired prompted the monitoring team to conclude that the department’s reform efforts with regards to policing itself were still woefully deficient.

“(There are) too many cases for too few investigators, investigations of minor allegations crowding out investigations of more serious allegations, inadequate and unreasonably tardy supervisory review of investigative findings, and lack of accountability for the timeliness and thoroughness of investigations,” the report states.