By Zenitha Prince

Senior AFRO Correspondent

1. Carter G. Woodson and the then-Association for the Study of Negro Life and History launched Negro History Week in February 1926. (AFRO Archives)

Socrates, the renowned Greek philosopher and sage, once urged his followers to “Know thyself.” Thousands of years later, that advice continued to resonate, becoming the underpinnings of Carter G. Woodson’s theories about the study of Black history.

“Carter G. Woodson was a visionary,” said Ibram Kendi, assistant professor of Africana Studies at the University of Albany. “He essentially sought to build within the Black community a greater consciousness of their history—the successes, failures, triumphs—all the complexities of African-American history.”

By all accounts, a young Woodson grew up poor in physical assets but rich in knowledge and wisdom. At his father’s knee, he learned about self- and race-pride…, that going through someone’s back door—a sign of inferiority—was never an option, no matter the cost. And from the Civil War veterans like his father, he also learned the lessons of self-determination and the value of Black contributions to the past and ongoing American story.

But, as Woodson looked within his community he noted those values of self-love, pride, self-knowledge, self-determination and self-worth were missing from too many. And, he placed the blame squarely on the “defects” of Western education, which was used as a tool to maintain the status quo.

“He believed that the negative ideas (Black) people had internalized about themselves were because of their ignorance about their own history,” said Professor Kendi.

Western education, from the elementary through the tertiary levels, had “mis-educated” many a Negro with propaganda and “heresy” about their so-called inferiority and lack of worth, Woodson posited. Even Harvard University, supposedly a bastion of first-tier scholarship, progressive thought and enlightenment, had “ruined more Negro minds than bad whiskey,” Woodson is quoted as saying.

The Black scholar elaborated on his theory in the seminal tome, {The Mis-Education of the Negro.}

“The so-called modern education, with all its defects… does others so much more good than it does the Negro, because it has been worked out in conformity to the needs of those who have enslaved and oppressed weaker peoples,” the book’s preface reads. “For example, the philosophy and ethics resulting from our educational system have justified slavery, peonage, segregation and lynching…. Negroes daily educated in the tenets of such a religion of the strong have accepted the status of the weak as divinely ordained, and during the last three generations of their nominal freedom they have done practically nothing to change it.”

Woodson goes on to explain, “No systematic effort toward change has been possible, for, taught the same

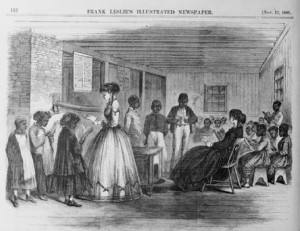

The Misses Cooke’s school room, Freedman’s Bureau, Richmond, Va., illustrated in Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper (Jas. E. Taylor/Library of Congress). Carter G. Woodson said the mis-education of Blacks regarding their history had been used as a tool of control.

economics, history, philosophy, literature and religion which have established the present code of morals, the Negro’s mind has been brought under the control of his oppressor. The problem of holding the Negro down, therefore, is easily solved. When you control a man’s thinking you do not have to worry about his actions. You do not have to tell him not to stand or go yonder. He will find his ‘proper place’ and will stay in it. You do not need to send him to the back door. He will go without being told. In fact, if there is no back door, he will cut one for his special benefit. His education makes it necessary.”

Black elevation and empowerment—in fact the very survival of the race—therefore, began with a sound education that included the teaching of true Black history, Woodson said.

“If a race has no history, it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated,” Woodson said in one of his articles. “The American Indian left no continuous record. He did not appreciate the value of tradition; and where is he today? The Hebrew keenly appreciated the value of tradition, as is attested by the Bible itself. In spite of worldwide persecution, therefore, he is a great factor in our civilization.”

Woodson began his quest to chronicle Black history and to legitimize scholarship in that field throughout his college years, but was often ridiculed and dissuaded by his professors and others. But in 1915, Woodson defies his critics—those leaders of Western academia and politics and a leery public who had long insisted Blacks had no history—by publishing his first text on African-American history, {The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861}. He takes it even further, later that year, when he also establishes the Association for the Study of Negro of Life and History (which later becomes the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.) Often going without a salary, Woodson led the organization’s efforts to research, uncover and publish their findings about Black life and history in the {Journal of Negro History,} a quarterly academic journal launched in 1916.

In 1926, Woodson and the ASNLH sponsored the first Negro History Week in February, which was meant to coincide with the birthdays of President Abraham Lincoln and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, both venerated figures in the Black community.

As with his earlier efforts to promote Black history, the observance initially was not widely received.

“There was a push in America at the time, particularly within academia, to unify all history as one—to create just one American story of the past, and usually that did not include Black history. When people did speak about Black history back then it was denigrated,” said Kendi, the Albany university professor. “For him to say we should appreciate it and celebrate it was revolutionary.”

Woodson’s vision of the Negro History Week went beyond his goal of educating African Americans about themselves—though that was part of his aim; it was also about educating others about the value of Blacks’ contributions to America and the world.

According to a Jan. 23, 1932 AFRO article, Woodson explained that the celebration of Negro History Week would be for nought if Black, White and all children were not given a chance to learn about all aspects of Black history in their schools.

“Unless Negro History Week can be used to accomplish such a purpose, the mere celebration would be meaningless. To have numerous essays and speeches on what we have done while failing to do this thing which is necessary for our present good will mean absolute failure so far as this observance is concerned,” he is quoted as saying in the article.

“The watchword throughout this season, therefore, should be to uproot propaganda in the minds of students and place in their hands certain works to inform them as to the contributions of all races. Interracial goodwill will be thereby stimulated, that this country may become a land of happiness and prosperity.”

With the passage of time, Negro History Week caught on, according to an essay by Daryl Michael Scott, president of ASALH: Black history clubs sprang up; teachers demanded materials to instruct their pupils; and progressive Whites, not simply White scholars and philanthropists, stepped forward to endorse the effort.

The “Black Awakening” and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s further amplified the importance of and interest in the historic contributions of African Americans. And, in 1976, the celebration was expanded to a month through a proclamation by President Gerald Ford, who urged Americans to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

Though Black History Month has since become a national fixture, there are some who question whether the observance is still necessary or even beneficial in what some have claimed as a post-racial society.

Experts say that is not surprising as it mirrors what some Woodson detractors have said from the beginning.

“If you look back now at his lifetime, most people assume his movement was widely embraced when it was not,” Kendi said. “He received a huge amount of resistance both within the Black community and outside.”

For example, among assimilationists, anything that played up racial differences was a no-no.

“There have always been Black people who view Black progress as Black people assimilating with Whiteness,” Kendi added.

In the presence of such self-effacing thought, persistent socioeconomic disparities and racism, Woodson would have likely argued that Black History Month, and its spotlighting of Black history and achievement, is very much an ongoing necessity, Kendi said.

“Carter G. Woodson would have looked at the persistent disparities and said that clearly we are not an inclusive society so long as we have White Americans, Black Americans and those of other races who see Black people as inferior there is still a need for multiculturalism and the study of Black history.”

CLICK BELOW TO SEE PUBLISHED WEEK 3 ARTICLE

http://issuu.com/afronewspaper/docs/week_3_afro_black_history_preservin?e=1066242/11488251